- January 31, 2020

- By Kimbra Cutlip

The ocean’s capacity to continue absorbing carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere is diminishing, decreasing its usefulness as a buffer against climate change, suggests a recent study led by researchers at the University of Maryland and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

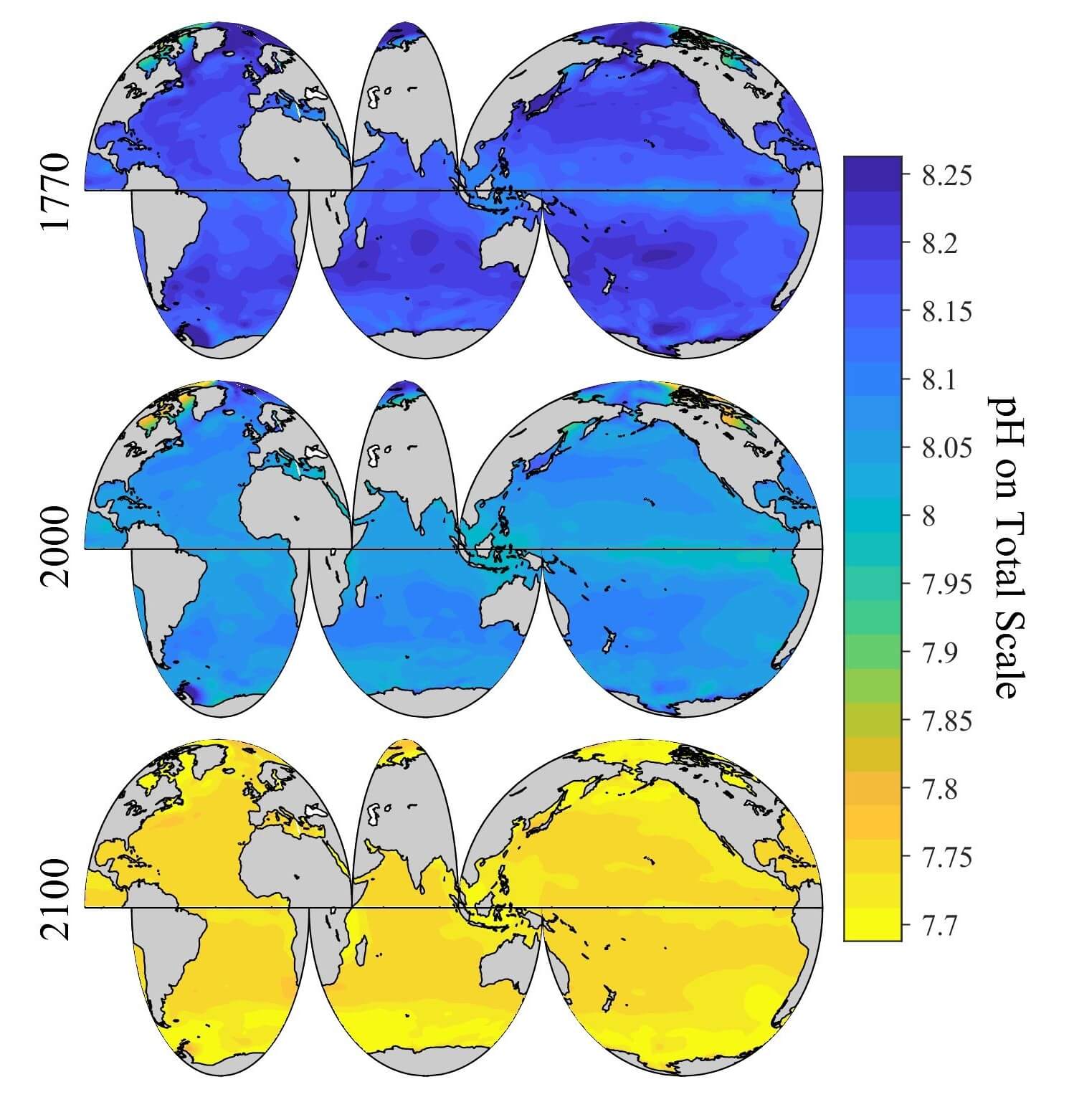

The international team of researchers created the highest-resolution maps to date showing changes in the acidity of seawater since the onset of the Industrial Revolution—a 270-year period during which the global ocean has absorbed the equivalent of over 600 billion tons of excess CO2 from the burning of fossil fuels, deforestation and other activities.

Their study, published in the journal Nature Scientific Reports, is the first to link modern observed pH data with modeled projections of CO2 emissions. The resulting images reveal increasing levels of ocean acidification occurring on a regional scale for all parts of the ocean, as greenhouse gas absorption changes the chemistry of seawater.

Their study, published in the journal Nature Scientific Reports, is the first to link modern observed pH data with modeled projections of CO2 emissions. The resulting images reveal increasing levels of ocean acidification occurring on a regional scale for all parts of the ocean, as greenhouse gas absorption changes the chemistry of seawater.

The study also projects that if CO2 emissions continue on the current trajectory, the ocean will slowly lose its capacity to be a climate-stabilizing “carbon sink” as ocean acidification increases.

In addition, lower seawater pH weakens the hard calcium structures within coral reefs and the protective shells of some invertebrate marine life. Previous studies have shown that ocean acidification has negative implications for coral reefs and marine ecosystems where shellfish play an important role.

According to lead author Li-Qing Jiang, an associate research scientist at UMD’s Earth System Science Interdisciplinary Center, and his co-authors, this research could lead to more preventive and adaptive solutions to reduce CO2 emissions, as the proportion of human-generated CO2 the ocean can absorb decreases.

“This is critical information that is important to share with regional government planners and activists interested in the current state of ocean acidity and its long-term trends in different parts of the world,” said Jiang. “I hope this work will serve as a warning and a guide that will provide the groundwork for policymakers and resource managers to develop regional adaptation strategies.”

In addition to Jiang, researchers contributing to the study are affiliated with NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information; the NOAA Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory; the Joint Institute for the Study of the Atmosphere and Ocean at the University of Washington; NORCE Norwegian Research Centre; Bjerknes Centre for Climate Research, Bergen, Norway; and Geophysical Institute, University of Bergen and Bjerknes Centre for Climate Research, Bergen, Norway.