- April 11, 2024

- By Annie Krakower

Students stir liquid simmering in five pots in a small lab tucked away in the Plant Sciences Building, with dozens of white fabric swatches swimming inside gradually taking on color. Some become a muted yellow, others a rich purple, and some assume an almost denim-like hue that turns greener by the minute. But this rainbow of results stems from just one reddish-brown source: logwood trees.

The hands-on dyeing experience is part of “The Quest for Color,” a plant science course at the University of Maryland that incorporates the chemistry, history and culture of plant- and insect-based dyes as students discover sustainable color creation.

“You measure the different ingredients, and you have an intent of where things are going to go, but the outcome is really somewhat stochastic,” said plant science and landscape architecture Professor Maile Neel, a trained botanist whose 30-plus years of experience dyeing silk and cotton fabrics inspired her to start teaching the class in 2021. “Although much of the outcome can be predicted based on chemistry and physics, there’s a really serendipitous element to it.”

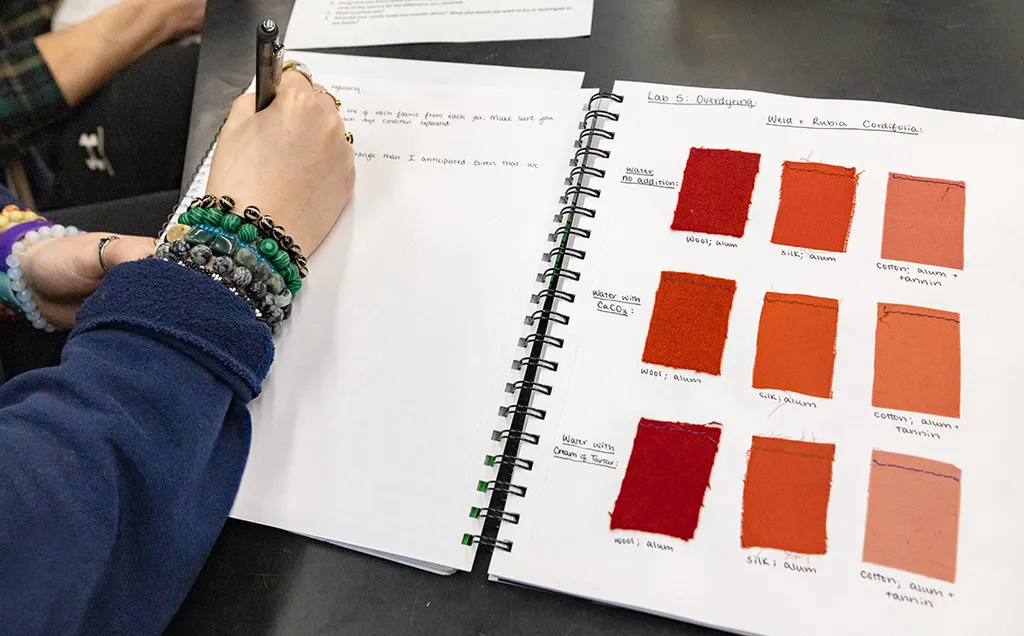

Each class starts with an overview of the chemistry behind that day’s “dyestuff,” whether that’s grounds from madder root, extract from weld plants or powder from indigo plants. Students explore how slight variations to the dye baths—like changing the acidity of the mixture or adding metal “helpers” like ions of iron or aluminum—create shades of difference. Acidic cream of tartar, they found, made the logwood solution yellow, basic calcium carbonate made it purple, and weld extract turned it green.

“That’s what I like about (this class)—you can learn all the little nitty-gritty,” psychology major Charlotte Gunther ’24 said. “If I see something that’s red, I can probably guess how they made that now. I can know exactly what contributed to that color.”

Most materials for the class come from natural dye supply companies, but for two weeks each spring, students collect plants across campus for their experiments. Leaves from the weeping willow by Memorial Chapel make a beautiful yellow, Neel said, wood ferns near the Physical Sciences Complex yield green, and coreopsis from the pollinator garden by Knight Hall creates an orange so striking it “looks fake.”

While delving into the dyeing process, she leads lectures on the historical and cultural contexts of the materials, some of which have been used for 5,000 years. In the 1500s, for example, cochineal, a red dye made from cactus-dwelling insects, caught the eye of Spanish conquistadors in Mexico, leading them to disrupt the system the local Aztec farmers had in place to send shipments back to Europe. The story is similar with indigo in Britain-controlled India.

“(The dyes) played a large role in colonization and what people were getting from these locations,” Neel said.

Although synthetic dyes have largely taken over the industry, artisan communities pushing for sustainable color have led to a resurgence of natural dyeing. Some “Quest for Color” alums have continued work in the field, including hosting natural dye art exhibitions in Europe and partnering with Indigenous groups in Bolivia to harvest plants for coloring.

For other former and current students, the class simply provides a scientific elective while allowing them to express themselves.

“It’s pretty inclusive for all majors,” said Karaline Benn ’24, who’s studying studio art. “The idea of finding pigments from nature and applying it to something you can use in real life is very exciting.”