- January 02, 2018

- By Chris Carroll

A North Carolina couple is gunned down in their house by a mysterious intruder.

A New Mexico mother arrives home to find a stranger looming over her savagely beaten daughter. He flees through a broken window, slashing himself.

A Texas woman is sexually assaulted and beaten to death, and police have no viable suspects.

Just a few years ago, crimes like these—where the only evidence available doesn’t match up with DNA databases or provide other useful leads—might have gathered dust in the cold case file.

Just a few years ago, crimes like these—where the only evidence available doesn’t match up with DNA databases or provide other useful leads—might have gathered dust in the cold case file.

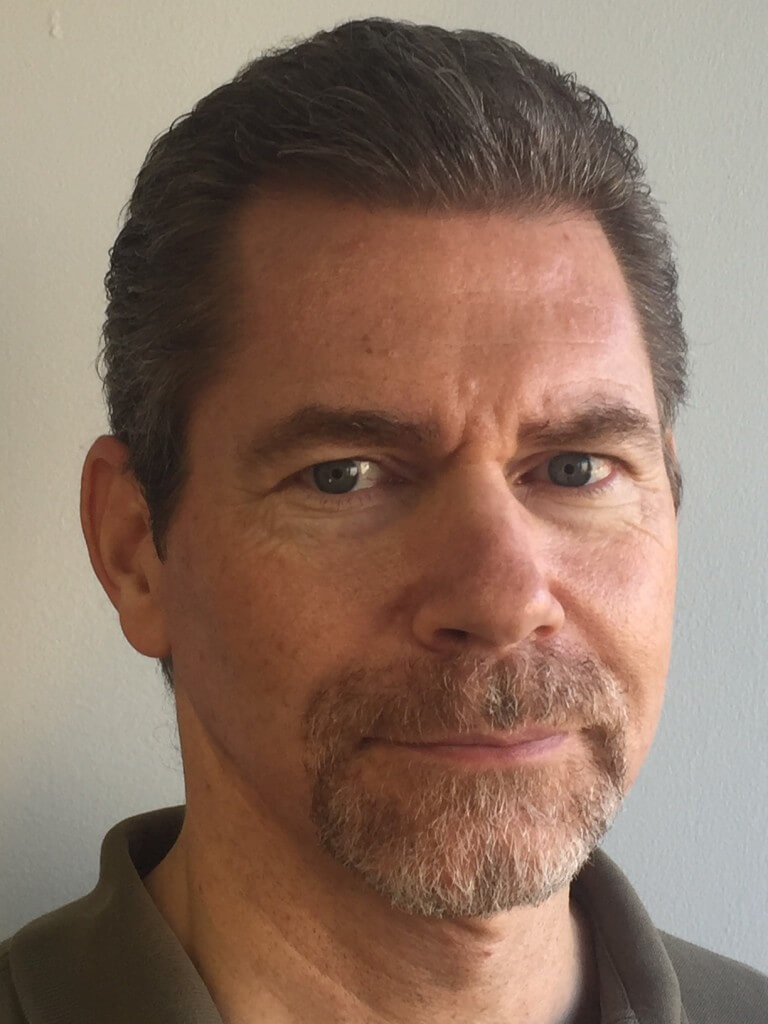

Not anymore. All these crimes were solved in recent months with the help of forensic technology developed by Reston, Va.-based Parabon NanoLabs, led by President and CEO Steven Armentrout Ph.D. ’94 (left), a University of Maryland computer science graduate.

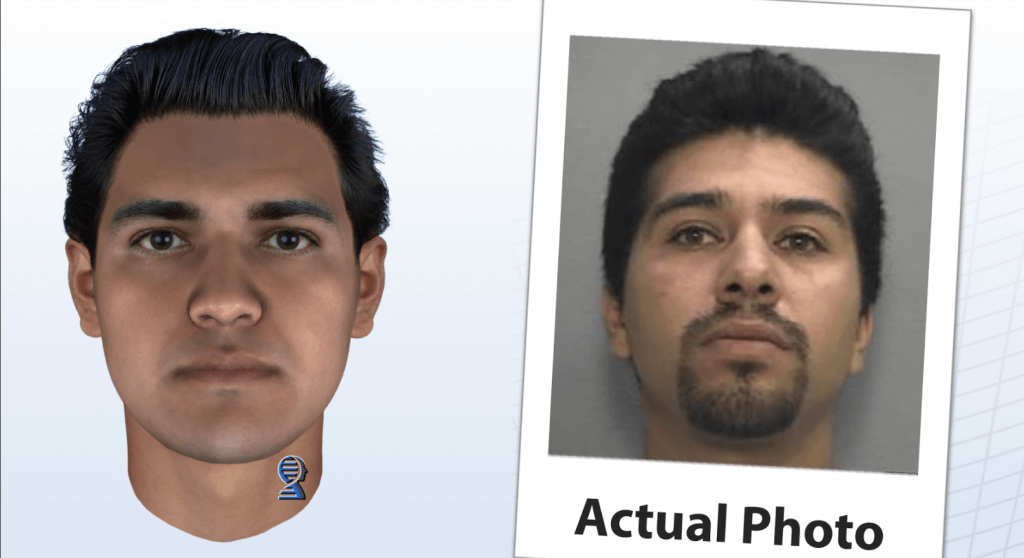

Known as Snapshot DNA Phenotyping, the technology, developed over a four-year period with support from the U.S. Department of Defense, seems more like an unrealistic plot device from a TV police procedural than a real-world investigative tool. What it can do is revolutionary: conjure a sometimes eerily accurate image of a face from a speck of genetic material.

“Think of a drop of blood so small it can barely be seen with the naked eye,” Armentrout says. “That will have at least a couple hundred cells, which is an ample amount of DNA to allow the comprehensive DNA phenotyping Snapshot provides.”

A phenotype is an observable trait in an organism; what Snapshot does is use high-performance computing to analyze an individual’s genome to find genetic variations known as single nucleotide polymorphisms, or SNPs, associated with different aspects of a person’s appearance, including face morphology.

In a process far more intricate than the standard forensic DNA analysis, the system uses advanced artificial intelligence and data mining to find SNPs that indicate ancestry and skin tone, and ones that predict eye and hair color, face shape and likelihood of freckling. At the end, the system spits out an image indicating what it thinks the owner of the DNA in question looks like.

Don’t take Armentrout’s word that it works; a 21-year-old Texas man stood up in church in November and confessed to the sexual assault and slaying of a neighbor after a Snapshot image based on his DNA was released in the community. Before the image was released, he wasn’t even on the radar of police investigators, but the accuracy of the image led the suspect to flee before ultimately surrendering.

“At this point, it has been used by hundreds of investigative agencies across the globe, and has helped solve some really high-profile crimes in this country,” Armentrout says, including the North Carolina break-in double murder and the New Mexico beating that left a teen girl with brain-damage.

Armentrout co-founded Parabon NanoLabs (PNL) in 2008 to focus both on forensics and development of customized, DNA-based pharmaceuticals, bringing expertise from decades in high-performance computing, working on problems ranging from genomic analysis to climate modeling to DNA nanotechnology. PNL is a subsidiary of Armentrout’s older company, Parabon Computation, which develops software that aggregates a company’s unused computing power so it can be put to good use.

“His ability to apply creative thinking to both business and technology is one of Armentrout’s greatest assets,” says James Reggia, a professor of computer science and his Ph.D. adviser at Maryland.

“The thing about Steve is that he not only keeps coming up with very novel ideas, but he also invests the time and effort to see those ideas through to successful applications and successful technical businesses,” Reggia says.

Although Snapshot has been put to use broadly in unsolved murder and rape cases, it has applications in non-criminal cases as well, such as identifying remains of war dead.

“The technology gets close but doesn’t provide an exact picture of a person,” Armentrout says, in part because some non-genetically-determined factors including scars, hairstyles and body fat play a role in appearance. It can, however, provide extremely high levels of certainty about what a person doesn’t look like, otherwise known as phenotypic exclusions.

“When we started, we didn’t provide exclusions,” he said. “For instance, we would say with 80 percent confidence this person has blue eyes. The cops’ response was, ‘Hmm, okay, but what can you tell us with 95 percent confidence?’

“That sort of drove us, out of frustration, to tell them we know with 99 percent confidence what the eye color is not; in this case, we know it’s not black or brown,” Armentrout says. “And they say, ‘Hey, that’s exactly what we need.’ Exclusions have been included in every Snapshot report since.”