- January 18, 2019

- By Liam Farrell

1

The night Ron Capps decided not to kill himself, he read a story.

It was 2005, and after a decade of working in war zones as an Army and Foreign Service officer, Capps had begun to suffocate under a blanket of guilt woven from the raids he hadn’t stopped and the villages he couldn’t save.

After stints in Kosovo, central Africa, Afghanistan and Iraq, Capps was helping train African Union peacekeepers during the Sudanese Civil War when he borrowed a pistol from a U.S. soldier, took two bottles of beer from his refrigerator, hopped into a Toyota pickup truck and drove west into the desert to die.

Then, serendipity in a luckless place. As recounted in his 2014 memoir, “Seriously Not All Right,” Capps had just loaded a bullet into the chamber and switched off the safety when his wife at the time called from thousands of miles away. The ringing cell phone stopped him from pulling the trigger.

“I’ll be careful, don’t worry,” he told her before driving back to town and returning the pistol. “I’ll be home in a few weeks.”

Once back in the United Nations guesthouse where he was staying, Capps picked up a collection of J.D. Salinger short stories and read one called “For Esme, With Love and Squalor.” In the story, a World War II veteran who suffered a nervous breakdown—“like a Christmas tree whose lights, wired in a series, must all go out if even one bulb is defective”—finds hope in a letter and package from a young orphaned English girl he met before heading to combat.

Since then, Capps has resided at the intersection of war trauma and the written word. A researcher at the University of Maryland’s National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START), Capps is also the founder and director of the Veterans Writing Project. His nonprofit, created in 2011, holds free writing seminars and workshops for veterans, service members and their families to build community and find healing through stories. More than 3,000 people in 22 different states have taken the courses, which will soon expand to include songwriting.

“Either you control the memory,” Capps says, “or the memory controls you.”

2

On a summer morning about 13 years removed from that night in the desert, a dog is snoring on the floor of Capps’ office. Harry, a rescued Labrador-hound mix once used as bait in a dog-fighting ring, has become a mascot of sorts for START, where Capps writes for the International Communication & Negotiation Simulations (ICONS) Project.

“I’m as much his service human as he’s my service dog,” he says.

With long gray hair, a beard and silver hoop earring, Capps looks more like a caretaker of wayward animals than a military officer. (He swears the hair isn’t a conscious rebellion.) The objects in his office tell that martial story—awards from the State Department and CIA, shrapnel and the nose cone of a rocket from Darfur, books on ISIS, Boko Haram and North Korea. One shelf mixes in some whimsy: finger puppets of dictators alongside action figures of “The Simpsons” villain Sideshow Bob and “Game of Thrones” heroine Brienne of Tarth.

Born in Florida, Capps was raised in the Navy town of Virginia Beach and surrounded by family who had served—his grandfathers had fought in World War I, some uncles in World War II and his father in Korea. He joined the Army in 1983, after bouncing in and out of college and making a go of it as a professional musician.

He spent time in the National Guard, patrolled the East German border in the waning days of the Soviet bloc and was trained in intelligence before joining the State Department as a Foreign Service officer. From 1995–98, Capps worked in central Africa, dealing with the aftermath of the genocide in Rwanda and the violence spilling over its border into Zaire.

It was during the Kosovo War as a diplomatic observer that he first gazed into the deepest abyss of human brutality. Living among civilians often targeted by soldiers, Capps would be one of the immediate responders to a village after an attack, when the air would reek from smoldering houses and decaying corpses and witnesses would be reeling in shock. Once, while inspecting a village with a colleague and a translator, his car was surrounded by armed Serbs; one held a pistol to Capps’ head before he was able to floor the accelerator and escape with his group.

“I knew somehow that Kosovo had changed me,” he says. “My emotions were a lot closer to the skin, but I was also a lot more empathetic.”

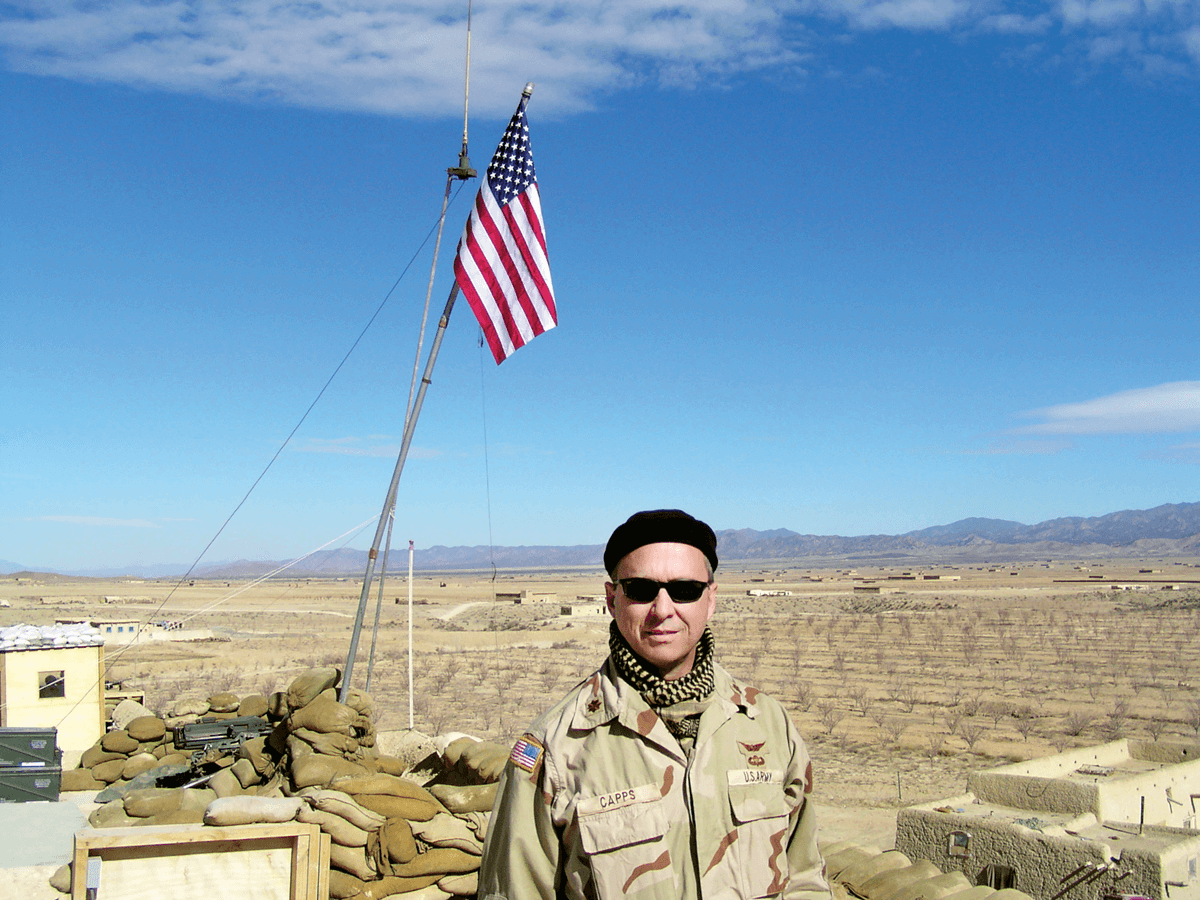

For a long time, his strategy for dealing with traumatic events was the well-worn military method of compartmentalization. Something bad happens? Put it in a box and fix it later. You have a job to do now. But by the time Capps arrived in Afghanistan in 2002, the mutilated dead were talking to him in his dreams, and his waking hours were wracked by panic attacks.

“There was a crack in the box,” he says, “and those memories started leaking out.”

3

After they started dating in August 2007, Capps would occasionally tell his wife of now 10 years, Carole Florman, that he was “crazy.” It was a description at odds with his trim government haircut, tailored suits and State Department job, which Capps had begun after requesting to be psychologically evacuated from Darfur.

“He was seemingly in terrific shape,” she says.

There were hints of his struggle, like anxiety in crowds at the 9:30 Club and a baseball game. But it was after Capps lost his security clearance for transferring files with a thumb drive to a classified network that she saw how consuming his post-traumatic stress disorder and depression could be. She remembers asking him: “Do I have to be worried that I’m going to come home and find you dead?”

Capps retired from the government, ending the official inquiry, and then began a master’s writing program at Johns Hopkins University. Hoping to help others through his education, he created the Veterans Writing Project.

“It started to reveal itself as something very worthwhile and therapeutic for him,” Florman says. “He has made very conscious efforts to identify, take hold and manage his struggles that are not only inward-looking, but meaningful for others.”

War writing in and of itself—what Union soldier and author Ambrose Bierce once termed the “phantoms of a blood-stained period”—has a long history in the United States, from Walt Whitman and Ernest Hemingway to Karl Marlantes and Phil Klay. Writing narratives allows an author to “(piece) back together the fragmentation of consciousness that trauma has caused,” says psychiatrist John Shay in his landmark 1995 book “Achilles in Vietnam.”

Capps wrote his 2014 memoir not only to heal himself but also in the hopes that going public with his story could reduce the stigma around asking for help. For many veterans, it is difficult to open up to the wider world: While the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs has reported a tremendous spike in disabilities due to post-traumatic stress disorder, tripling in a decade to more than 940,000 cases in 2017, the share of the U.S. population with military experience has plummeted, according to the Census Bureau, from 18 percent in 1980 to 7 percent in 2016.

The Veterans Writing Project steps into this gap. Seminars are held around the country in college classrooms, public libraries and arts council meeting rooms, generally lasting two days and covering basics of storytelling like dialogue, scene-setting and plot development. Classes include as many as 25 students and as few as four.

“What stands out (among veterans) is an eagerness to be able to tell stories and not be judged,” says Capps, who teaches along with three other veteran writers and consulted with Shay and prominent psychiatrists on the curriculum.

M.L. Doyle, who served 17 years in the Army Reserve and helped write the 2010 memoir of the United States’ first black female prisoner of war, attended a workshop in 2012 and has since self-published mystery and romance novels. Writing is a solitary pursuit, Doyle says, so gathering with other aspiring veteran-writers was motivating and built confidence.

“There is a very active, very vibrant veteran writing community I never knew existed,” she says. “You’re speaking the same language. All you have to do is say, ‘Kandahar,’ and people know what that means.”

4

In February 2012, 51 days after her deployment to Afghanistan as a human resources officer ended, Lisa Barber boarded an airplane for Marrakech, Morocco.

As she recounts in “I Was There,” a story written for O-Dark-Thirty, the Veterans Writing Project’s literary journal, she was overcome by anxiety on the plane ride and curled into a ball on the tiny bathroom floor, trying to distract herself by naming bands and musicians for each letter of the alphabet, and sipping a can of Pepsi brought by a concerned flight attendant.

“The Army spent three months training me for the worst possible day, and I was 100 percent convinced the worst possible day was going to happen,” Barber says. “I had a very hard time turning off that fear.”

The writing seminar she took in 2013 came along when she “needed something positive to do,” and she stays in frequent contact with her instructor.

“(Capps) really has done an amazing job at building a supportive community,” Barber says. “There are still lots of struggle days. There are also lots and lots of great days, and there weren’t (before).”

In his job at START, Capps is part of a team that develops war games and other policy simulations for education, government and private sector and nongovernmental organization clients.

“Ron has the perfect profile. He has all the background and credibility you need,” says Devin Ellis, the director of ICONS. “On top of it all, he’s a phenomenal guy.”

Capps has also gone back to school full-time to create a songwriting curriculum for the veterans project, taking online courses through the Berklee College of Music on music theory, digital recording, guitar and piano. When completed, he envisions adding music composition and lyric classes to the Veterans Writing Project repertoire.

Each week, he teaches writing for Creative Forces, a National Endowment of the Arts program at the National Intrepid Center of Excellence, the Department of Defense’s top research and treatment institute for PTSD and traumatic brain injury in Bethesda. It has a similar curriculum to the Veterans Writing Project but is geared more toward just engaging them in creative writing as an emotional outlet; a typical class would be writing for 15 minutes about an important personal memento and, if anyone wants, sharing it with other students.

Capps is an evangelist for the healing power of the arts. Confronting traumatic memories is like touching a hot stove, he says; by applying a new skill against the evolutionary impulse of sensing danger, you are putting a glove on your hand first.

“Writing,” he says, “is that protection.”

Barber thinks it may be time for her to take another seminar from Capps’ project. Part of her is cautious—she works from home to avoid commuter crowds and Metro tunnels, and wonders if confronting old memories could re-trigger some of her worst symptoms.

But she also misses the catharsis of the seminars and being around people who knew, without knowing, her story.

“It helped me feel a little less special,” Barber says. “That’s good.” TERP