- January 15, 2016

- By Chris Carroll

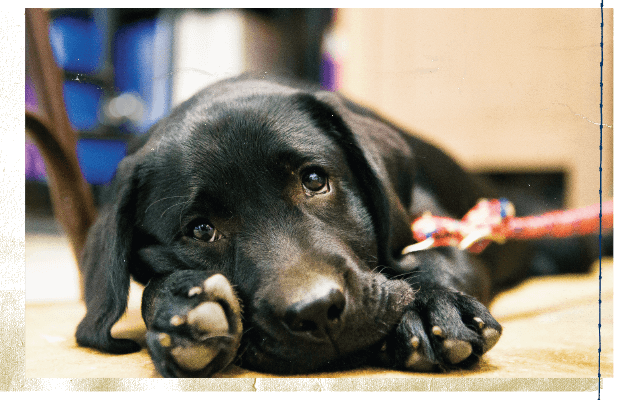

The golden retriever puppy gazed up at Abel Rosas with adoring eyes, then tried to clamber into his lap.

“Get the f— off me,” the 26-year-old Marine corporal growled, recoiling.

It was 2008, two wars were boiling in the Middle East, and he belonged over there with his fellow infantrymen hunting terrorists. Not playing with a dog in a California post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) treatment center.

Homecomings from war were always bad—bills to pay, the tiresome spit-and-polish of garrison life, demands from his fiancée. His solution was mental retreat from everything, even the love of the woman he relied on for long-distance support during deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan.

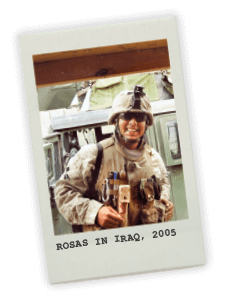

But now the thing that had given his life meaning, combat, was gone. After a roadside bomb nearly killed him in Iraq, doctors diagnosed brain injuries and declared him unfit for battle. Rosas exploded, savagely attacking an officer in hopes he’d be killed by military police.

Instead of prison, the Marine Corps sent him to the National Center for PTSD to heal. Rosas arrived angry, refusing to participate in rehabilitation. Commitment in an inpatient psychiatry unit seemed likely when a social worker tried something new.

The puppy, Vegas, was unfazed by Rosas’ rebuff and reared up on his lap, begging for attention. Rosas nearly jerked away again. But looking into the dog’s gentle eyes, he felt an unexpected sense of peace, and the beginnings of an idea: Maybe he could get better.

For the first time since his combat disqualification, the Marine smiled.

Modern science has confirmed what dog lovers know intuitively: There’s a unique biological bond between our two species. Now, a UMD researcher and his students are studying whether that connection can help heal families of military veterans with PTSD.

Norman Epstein, a professor and director of the School of Public Health’s Couple and Family Therapy Program, is spearheading a key part of a sprawling, military-funded four-year study nicknamed “Big Dog.” It will place hundreds of active-duty military members undergoing PTSD treatment at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Md., and at Fort Belvoir, Va., in a program training service dogs for placement with disabled veterans.

A large team of researchers—Epstein is the rare civilian among them—will monitor physiological, psychological and behavioral signals to see if dogs can be therapy tools for those suffering the invisible wounds of war, like severe anxiety, disturbing flashbacks and self-imposed isolation.

PTSD is widespread after 14 years of war since the 9/11 attacks. The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) estimates that up to 20 percent of the 2.7 million Americans who served in Iraq and Afghanistan show symptoms. And while direct correlation is impossible, it’s undeniably played a role in skyrocketing rates of family tragedies during the worst years of fighting, including a military suicide rate that more than doubled and a 42 percent increase in divorces.

“There’s certainly anecdotal evidence that working with training the dogs and having that attachment counteracts PTSD symptoms—it brings people out of their shell and seems to help reduce some of their emotional reactivity symptoms,” Epstein says.

Family Connections

The sobering statistics are what make Epstein’s contribution to the study critical to defense leaders. Military families will come to his center for assessments before and after a six-week dog training session, and continue the visits for a year to see how long the canine effect lasts.

Each visit, they’ll be filmed doing activities with their children and discussing sources of discord with partners. The videos will be turned over to teams of “coders”—undergrads who Epstein trains to spot every subtle and not-so-subtle sign of positive or negative attitudes and communication.

“With couples, they’ll be looking for, for example, validation and invalidation behavior, verbal and nonverbal,” he says. “One person says something and the other responds, ‘Oh, that’s silly.’ Nonverbal would be rolling of the eyes or looking up at the ceiling when the partner is talking.”

Epstein’s doctoral students, Jennifer Young M.S. ’14 and Shawn Kim M.S. ’15, are responsible for interacting with families and carrying out many of the procedures. He’s been honing the basic protocol for years; his methods to objectively measure domestic dynamics have made him a worldwide leader in couple and family therapy.

The current-events component of the research makes it a bit unusual, Young says, but there’s something else too.

“I want to play with puppies,” she admits.

That’s part of the appeal for Epstein, a dog lover himself. Although the low-key professor’s boisterous Chihuahua and terrier duo bear little resemblance to the large, calm retrievers frequently used as service dogs, he was drawn to the research by curiosity about how canines affect the human psyche.

“When I’m with my dogs, it’s a good feeling, it’s calming, and there’s a strong feeling of connection,” he says.

Clinical studies back up the power of the human-dog connection. A 2015 report by researchers at Azabu University in Japan, for instance, shows that—like new mothers and babies—dogs and humans experience a release of oxytocin, known as the “bonding hormone,” when they gaze into each other’s eyes.

How does bonding with a dog actually help military families experiencing PTSD?

The key to the new study is that the service members won’t just be hanging out with dogs, but actively training them as service dogs, says Dr. Paul Pasquina, a retired Army colonel and the primary investigator for the Big Dog study.

“In the process of learning how to train a dog, they’re engaged in tasks that require concentration, attention, communication skills, picking up on the sensitivities and the difficulty of training a dog,” says Pasquina, chair of the Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation at the federal Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda.

Those same skills may also heal families, Epstein says.

“When you have a person who’s startled easily, who’s easily irritated and becomes angry and lashes out frequently—it’s stressful to be around them,” he says. “But working to train a dog, they have to develop empathy and understanding of the dog’s frame of reference. And we think that might generalize to developing empathy and understanding for their children and spouse.”

It had dramatic results for retired Coast Guard Lt. Thomas Faulkenberry, a special operations member who arrived at Walter Reed in 2013 with a battered body and bottled-up emotions after 15 years in the service.

He’d returned from post-Hurricane Katrina rescue operations in New Orleans wracked with anxiety, says his wife, Mary Faulkenberry.

“He was always the life of the party, someone who could make friends with anyone,” she says. “But he came back with a dark cloud over him—cynical, hypervigilant, just changed.”

He began drinking heavily and relying on pain pills for injuries and other physical ailments. His relationship with his wife and four sons was tattered, and suicide was on his mind.

Service dog training was part of his rehabilitation at Walter Reed. When he carried home the methods of positive reinforcement he was instructed to use training dogs, his distant, heavy-handed manner toward his family changed.

“It was almost immediate, and it was a positive impact,” Faulkenberry says. “The training is focused on positive reinforcement… it was ‘fake it until you become it.’ Until you can actually feel that enthusiasm and happiness, that’s how you act.”

Saying Yes

Abel Rosas was sure he knew a few things about training. As a sergeant, he’d commanded squads of junior Marines through the worst battles of the Iraq occupation. But he’d been demoted to corporal for driving drunk and fighting after coming home.

Rosas grew up in a harsh and broken home. Training his men, he used the tools he knew: terse commands followed by screaming and threats until they got it right.

His attitude spilled into his relationship with Claudia, his wife since 2009. “More than anyone else, my wife has borne the brunt of my transition.”

Screaming wouldn’t work with Vegas or other service dog trainees, says Rick Yount, the social worker who’d slyly sicced the affectionate 8-month-old puppy on Rosas, then watched the reaction from the corner of his eye. Not only had the Marine emerged from his self-imposed isolation, he’d agreed to try training dogs.

The dogs are warm and gentle, so Rosas would have to be gentle himself, Yount told him. When they do something right, he told Rosas, praise must be immediate—and crucially, it must be high-pitched for a puppy to grasp it as positive feedback.

“It’s ‘Yesss!’” the burly Yount squeaked in a voice two octaves higher. “Channel your inner Richard Simmons.”

Yount founded Warrior Canine Connection, a nonprofit that trains service dogs for disabled veterans. For several years, the Brookeville, Md.-based organization has involved troops with PTSD in the multiyear training process as a form of therapy. Now its dogs and staff instructors are part of the Big Dog study.

Rosas in 2008 was the first “warrior trainer” Yount worked with, and like many since, he struggled to soften his demeanor toward the dogs. Reminding troops of the objective of the program—the mission—breaks down their resistance, Yount says.

“You say, ‘Let’s not talk about your problems—let’s talk about the veteran that needs help from this dog you’re training,’” he says. “Maybe they feel they don’t deserve to get better. [Service dog training] is a way of flanking that resistance with this mission-based program to help another veteran.”

Rosas worked to develop his suppressed empathy so he could connect with Vegas and be a better trainer. But after Rosas completed his rehabilitation program and medically retired from the military, he again spiraled into anxiety and depression.

Then in 2009, his janitorial business went bankrupt. He went to a Texas oilfield to kill himself, but his gun misfired. In a moment of clarity, Rosas realized he needed help. As he resumed PTSD treatment through the VA, Yount called to offer him Vegas permanently. They were reunited in February 2010.

“I started to do all the old training things I’d done with him,” he says. “Vegas saved me. I’d be dead now without him.”

Rosas’ son, Nico, was born the following year. The stress of new fatherhood set him on edge, he says, but the emotional self-control he’d learned working with Vegas helped him avoid recreating the abusive environment he’d grown up in.

This year, Rosas received a master’s degree in social work from California State University San Marcos and now assists veterans in crisis through the San Diego nonprofit Courage to Call.

“A few years ago, I didn’t think I’d ever be helping people in the same situation I was in,” Rosas says. “I take Vegas with me a lot—it just helps when he’s there.” TERP

Tags

Student Experience