- June 29, 2025

- By Chris Carroll

THE GLENN L. MARTIN WIND TUNNEL opened in secret at the dawn of the Cold War. A gift to the University of Maryland from the aircraft industry titan whose name it bears, the facility was used to develop U.S. military planes and missiles for a looming showdown with the Soviet Union. Long since declassified, it still works with government agencies as well as civilian companies, though it might be best known locally for giving guests a hair-whipping thrill at UMD’s annual open house.

Early this year, the 76-year-old facility briefly slipped back into its shadowy security role. University officials gave the startup company Patero, based in a UMD business accelerator, a chance to test its technology by locking down the tunnel’s computer systems—not against midcentury spycraft, but a futuristic form of cyberattack that doesn’t yet exist.

The work lay in the quantum arena, where firms and nations are racing to introduce the first powerful quantum computer, a machine that could potentially sow chaos by quickly defeating currently invulnerable data security measures. But it could also be used to create revolutionary, life-enhancing advances in pharmaceuticals, ultra-secure networking, the fabrication of new material with unheard-of properties, and other areas.

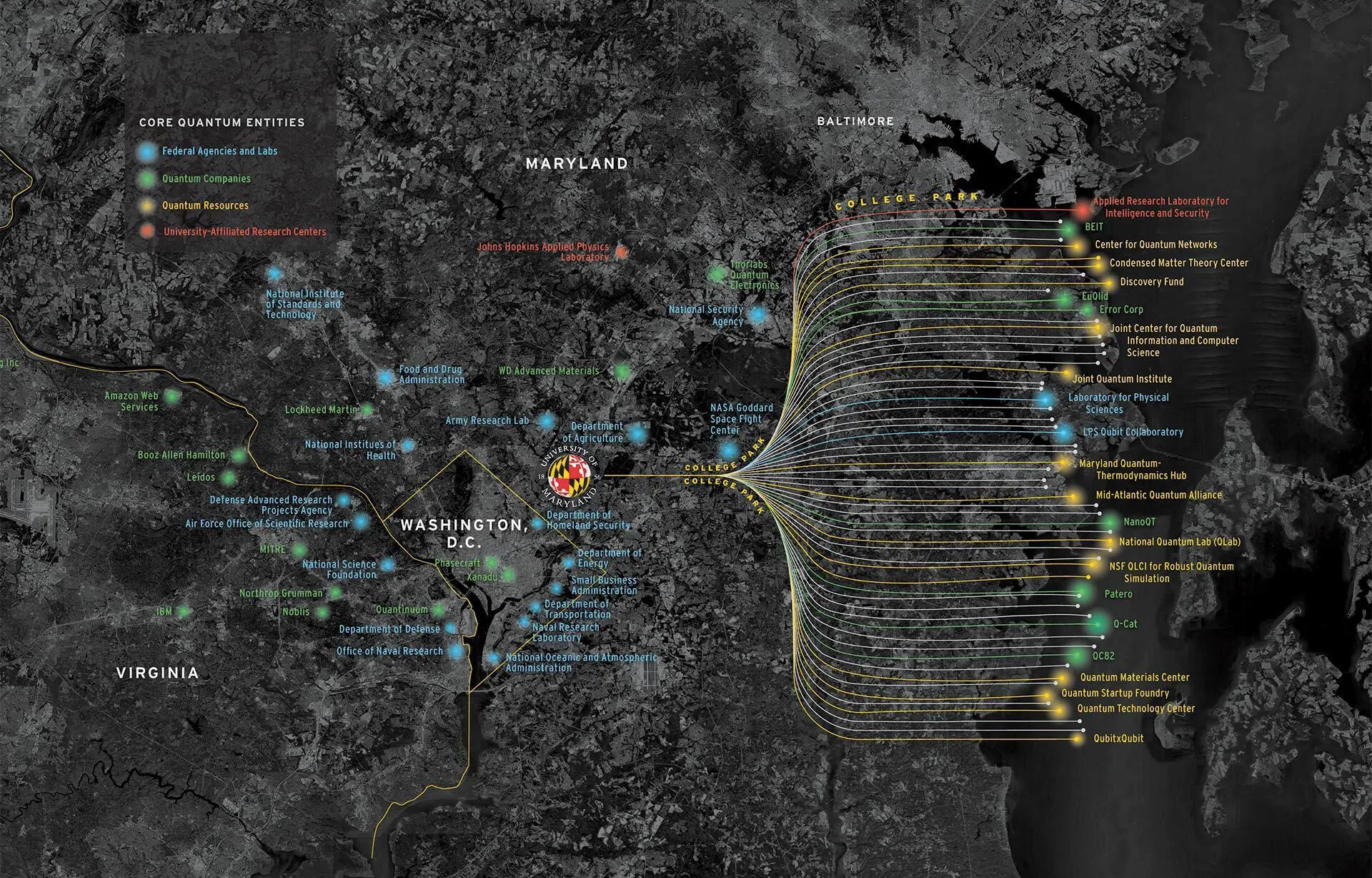

To help ensure society reaps these benefits while fending off risks, the University of Maryland is redoubling its efforts, along with the state and a range of business partners including Patero, to cement the region as a global hub of quantum research and innovation.

Gov. Wes Moore announced this strategic initiative, dubbed “The Capital of Quantum,” in January. It includes plans to attract $1 billion in investments over the next five years to support quantum research and training across the university and beyond, including new faculty hires and facilities; a deepening of the relationship with IonQ, a world-leading quantum computing and networking firm spun off from UMD research and headquartered in the university’s Discovery District; support for academic degrees and educational programs to help expand the quantum workforce; and investment funds to grow the expanding ecosystem of quantum startups and firms around College Park.

“With extraordinary assets and partnerships, Maryland can—and should—lead in this new emerging sector, and we are moving forward with a clear strategy to make that vision a reality,” Moore said at the initiative’s launch event at IonQ.

The funding will come from a combination of state funds, matching federal grants, private-sector investments and philanthropic contributions, and includes an initial $27.5 million submission in Moore’s FY26 state budget request that is expected to catalyze an additional $200 million in state funds from the university and its partners.

Quantum Foundations

UMD President Darryll J. Pines coined “the Capital of Quantum” as a geographical call to action, playing on the university’s advantageous location adjacent to Washington, D.C., and its reputation as the site of many quantum discoveries over the decades.

“A few years ago, I realized this worldwide competition was developing around quantum,” he says. “We have to maintain the university’s academic lead in this area, and we can’t let the state of Maryland lose out on the economic benefits of this potential industry as it emerges.”

Quantum science itself isn’t new—Einstein and other physicists explored how matter and energy at the scale of atoms and below make up the universe more than a century ago. Later, their discoveries formed the basis for transistor radios, computers, medical imaging machines and more.

In 1994, “quantum” assumed a broader meaning when computer scientist Peter Shor of Bell Labs demonstrated a quantum algorithm that allowed for an exponential speed-up of prime number factoring, which is the basis of data encryption, but only with the right hardware.

“That’s what really stimulated everyone everywhere to start thinking about this: How do we build a quantum computer?” says Steven Rolston, professor and chair of UMD’s Department of Physics.

UMD was already strong in basic physics research, and its physics department soon struck up a more formal link with the National Institute of Standards and Technologies (NIST), in 2006 combining to launch the Joint Quantum Institute (JQI) with UMD’s Laboratory for Physical Sciences as a third partner. JQI quickly grew into a major center of quantum theory and experimentation, with more than 200 scientists and scores of Ph.D. students each year turning out hundreds of publications. In 2014, NIST and UMD launched the complementary Joint Center for Quantum Information and Computer Science (QuICS), which shares many faculty and fellows with JQI.

“This really puts us at the top in terms of quantum research,” Pines says. “They very intentionally and strategically brought in people from across the important domain spaces in quantum. That led to the recruiting of a young faculty member who helped push things to the next level for UMD.”

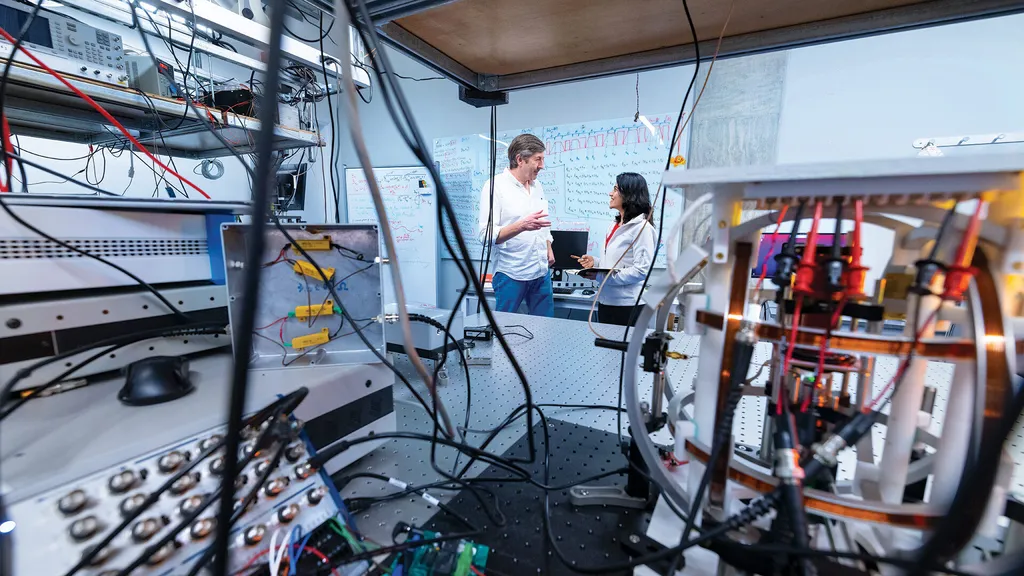

That faculty member was physics Professor Christopher Monroe, hired at UMD in 2007. Early on, he made headlines around the world for using atoms to “teleport” quantum information across space using quantum entanglement, in which particles are “linked” so that what affects one affects both. Entanglement was also part of what allowed Monroe and colleagues to use ions of the element ytterbium as natural “qubits.” These are the quantum equivalent of “bits,” which are represented by zeros and ones in regular, or “classical,” computers. Unlike classical bits, though, qubits counterintuitively can represent a zero and one at once, opening the possibility of vastly accelerating calculations.

The Unicorn

Along with collaborator Junsang Kim of Duke University, Monroe founded IonQ in 2015. (Both have returned to academia full-time as professors at Duke.) The fledgling firm received financial backing after venture capitalist Harry Weller, a general partner at New Enterprise Associates, delved into Monroe’s “trapped ion” computing research. Before long, the tiny startup was making waves with its early-stage quantum computers and was being mentioned in the same breath as giants like Microsoft, IBM and Google in the race to build the first broadly useful quantum computer system.

After years of expansion, the firm debuted on the New York Stock Exchange in 2021 as the world’s first publicly traded “pure play” quantum hardware and software company; it was valued at more than $1 billion as it prepared to enter the exchange, aka a “unicorn.” Early in 2025, the company’s value reached 10 times that amount.

In the back of the company’s headquarters off Campus Drive, technicians exactingly assemble quantum processors in a clean room, while giant racks of quantum computers in another room serve customers around the world looking to stay current on the state of the field. A next-gen computer slated to come online late this year will nearly double the number of qubits in IonQ’s flagship machine, which the company expects to boost computing power to about 250 million times that of the current computer. That should be game-changing in terms of moving quantum computers from objects of study to useful tools—not replacing conventional computers, but starting to be necessary alongside them, says the company’s chief financial officer, Thomas Kramer.

“It will be a computational power the world has not yet seen,” he says. “At that point, we think use cases (for quantum computing) will start to become more obvious.”

In true startup fashion, IonQ is based in a repurposed warehouse, but intends to relocate to a new headquarters in the Discovery District, a move the university is helping to support.

Other plans call for an expansion at the company’s current location of an IonQ-UMD collaboration—the National Quantum Laboratory at Maryland (QLab). This user facility provides an opportunity for researchers from around the world as well as UMD students and others to access IonQ’s quantum computing technology and interact with its experts. Former UMD quantum scientist Norbert Linke, who helped develop trapped-ion computing, will return to the university this fall to serve both as QLab director and a professor of physics.

The QLab is a node on Mid-Atlantic Region Quantum Internet (MARQI), which was designed by Professor Edo Waks and Tripti Sinha, assistant vice president and chief technology officer with the Division of Information Technology. With funding from NSF, it has more than 2 kilometers of fiber optic cable that extend across UMD, serving as a testbed for quantum networking technologies that will enable the transmission of quantum information using current “classical” Internet infrastructure.

“The Internet has proven the power of aggregation and distribution by networking resources, and we believe we can build on quantum computing the same way,” Sinha says. “It’s still in the future, but the University of Maryland could be poised to be the first place where quantum computers communicate on a network.”

At IonQ HQ, Kramer points to a wall of plaques commemorating IonQ’s hundreds of patents, evidence of a company that is surging.

“As the company grows and matures, more patents have now been generated by IonQ as opposed to coming from our university partners, which shows our commitment to generating new, groundbreaking IP in-house,” he says.

Reaping ‘Capital’ Gains

What’s needed now is infrastructure—backed by UMD and the growing regional quantum ecosystem—for companies to build on the promising commercial foundation IonQ has been laying.

Its rise as a publicly traded spinoff quantum company was a towering achievement for UMD—a feat no other university or group trying to create a quantum hub elsewhere has replicated, says Ronald Walsworth, a professor of engineering and physics who directs UMD’s Quantum Technology Center (QTC).

“Realistically, we’re probably not going to get another IonQ anytime soon—but we can help grow additional successful companies across the quantum ecosystem,” he says.

The focus of QTC is to “innovate, translate, and educate in quantum technology,” Walsworth says. He and his colleagues and students focus on the wide range of promising quantum innovations—not just quantum computing. Walsworth is widely known for his work in MRI and sensing, while others in the center (including Waks, the associate director) focus on creating quantum networks, which could promise ultimate communications security when linking quantum computers.

Walsworth’s own startup, Quantum Catalyzer (also known as Q-Cat) currently sells an invention from his and his colleagues’ labs—the quantum diamond microscope, which harnesses atomic-level faults in diamonds to allow unprecedented views of everything from microelectronics to ancient meteorites to biological samples. In turn, those sales help Q-Cat, which was primarily conceived as a quantum business incubator, to support the development of other quantum startups; its first spinout company, EuQlid, uses the quantum diamond imaging technology in inspection for flaws in advanced semiconductor chips.

If the Capital of Quantum Initiative succeeds in attracting new sources of private capital—Weller jumping on the IonQ train early was a key factor in the company’s success—the quantum hits should keep coming for UMD, Walsworth says.

Funding opportunities—existing and hoped-for—brought another startup to UMD. QC82, a University of Virginia quantum computing hardware spinout, was lured by the opportunity to join the Quantum Startup Foundry, launched in 2021 to guide startups confidently through their early steps, whether obtaining office space, finding investors or navigating paperwork.

“We take a very bespoke approach, one that is extremely tailored to the company,” says Piotr Kulczakowicz, QSF director. “We define their needs and assess how we can help them with their needs, and then we are there to help in too many ways to list, really.”

QC82 also received an investment from UMD’s Discovery Fund, which distributes up to $1 million a year to innovative startups. One of only two photonics quantum computing startups in the country, QC82 touts core technology that allows room-temperature computing, unlike many competitors that must chill their qubits to near absolute zero.

“We’re here because essentially the best place for quantum on the East Coast wanted to invest in us,” says Hussain Zaidi, QC82’s CEO. “What we do is very hardware-intensive; it requires significant capital to bring revolutionary technology to market. The vision that the university and the state are showing by making this long-term commitment will go a long way to attracting investors that companies like ours need.”

A Stake in the Ground

The Capital of Quantum initiative brings a laser-like focus to leverage decades of related achievements, Pines says.

“The governor’s announcement here at UMD puts a competitive stake in the ground that says here’s what we intend to build: an emerging industry with the University of Maryland and all its strengths in quantum at the center,” he says. “This will bring great economic benefits for our state along with immense potential to create solutions to some of the world’s pressing problems.”

Projections of global quantum spending in coming years are eye-popping, says Ken Ulman, UMD’s chief strategy officer for economic development and president of Terrapin Development Co., a partnership between the university and its nonprofit financial arm that is leading several local quantum projects. McKinsey and Co. recently estimated the market size could reach $90 billion within a decade, with up to a $2 trillion economic impact across the chemical, life sciences, transportation and finance industries.

Within two weeks of Moore’s announcement, more than a dozen U.S. and international companies contacted the university to line up tours and talk about joining the growing hub, Ulman says. UMD’s slate of offerings is compelling: office space in its increasingly vibrant Discovery District alongside federal science agencies and IonQ, the QSF’s business development programs and an ecosystem featuring hundreds of quantum researchers—plus graduates to potentially hire.

“With our unique strengths in quantum, why wouldn’t we go after this?” Ulman says. “When you look at all the attributes, we’re one of the few places in the world where you could actually build something worthy of being called the Capital of Quantum.”

Beyond business support, UMD’s physics department has long prepared graduates for quantum careers in government labs and the tech industry. In recent years, other parts of the university, including engineering and computer science, have joined in to train the quantum workforce the U.S. needs to compete in this important arena.

UMD recently launched a Master of Science in quantum computing program and its new program in quantum science and engineering will begin as a minor to provide footholds for undergraduates to enter dynamic careers.

Peter Bentley ’88, chief operating officer of Patero, the company that tested its “post-quantum” cybersecurity suite at UMD’s Wind Tunnel, says the university’s support has helped put his College Park-based company in a leading position as firms and government agencies begin contending with the risks and opportunities of the rise of quantum, and move to secure their online presence.

“This market is about to flex, and as an alumnus, I kind of love it that Maryland wants to lead this,” Bentley says. “Because of the level of support we’ve gotten from the Quantum Startup Foundry, and the way the university has aligned itself with its government partners, Patero is now the first post-quantum company out of the gate.”

This article is featured in the latest issue of EnTERPrise magazine. Read more at research.umd.edu.