- April 15, 2014

- By David Kohn

The genetic mutation that has prompted thousands of women, including actress Angelina Jolie, to have preventive mastectomies may also have effects on other tissues, according to a new study by a School of Public Health professor.

The gene, known as BRCA1, is not well understood, even though it exists throughout the body, not just in breast and ovarian tissue. But researcher Espen Spangenburg and others have found that it appears to be involved in storing fat in muscle cells, and its malfunctioning may play a role in other health issues besides cancer, including obesity, diabetes and metabolic problems.

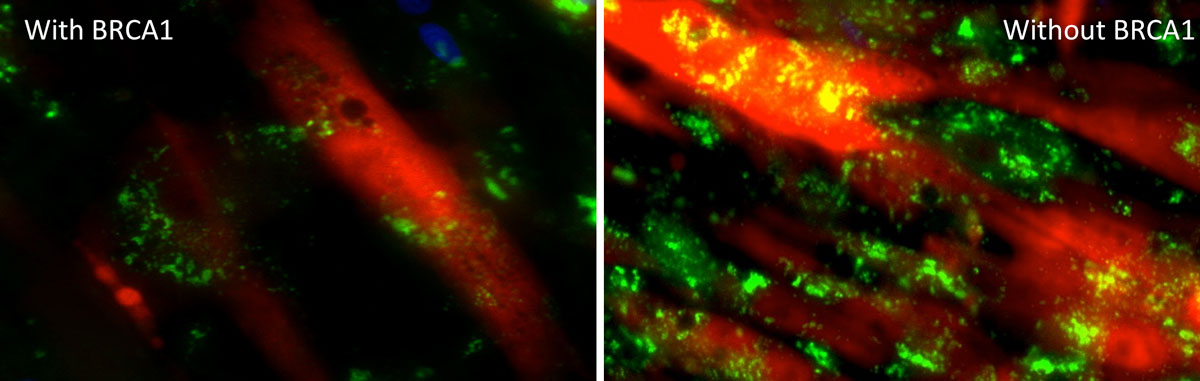

The study established for the first time that BRCA1 is expressed in muscle cells. Spangenburg and scientists at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, Brigham Young University, East Carolina University and the Karolinska Institute in Sweden tested their theory on the BRCA’s role by inactivating BRCA1 in isolated human muscle cells, The result: The muscles stored more fat and less glucose, and thus became more fatty.

“We took a healthy muscle and made it unhealthy,” says Spangenburg, a cell biologist in the Department of Kinesiology.

The findings are especially intriguing because obesity and many kinds of cancer have long been linked. Spangenburg says BRCA1 could play a role in both conditions. It is not clear how muscle and metabolism problems might be linked to cancer; breast and ovarian cancer may have some relation to disorders of energy storage.

“This is trailblazing work,” says Priscilla Furth, a cancer research and doctor at the Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center at Georgetown University. “It opens up a new box. What is BRCA1 doing in other tissues? This is an important gene.”

Breast cancer is most common form of cancer in women: About 12 percent of women in the U.S. will be diagnosed with the disease, according to the National Breast Cancer Foundation. The illness is the second-leading cause of death for women in this country. Every year, 220,000 are diagnosed, and 40,000 die.

Research on the BRCA1 gene, which was discovered in 1994, has shown that it accounts for 70 percent of all cases of inherited breast cancer. Certain BRCA1 mutations increase the risk for several other cancers, including prostate and pancreatic.

Between one in 400 and one in 800 people in the U.S. have a cancer-related BRCA mutation. In some groups, the variation is much more common: Among Jews of European descent, the rate is about 10 times higher.

While the new results are promising, they complicate the picture for BRCA1 researchers. The gene has more than 1,000 mutations, Spangenburg notes, and “we don’t know what most of them mean.” It is not clear which of these variations are involved in cancer, and which might be involved in muscle function. He says the versions correlated to cancer may be the same ones linked to muscle damage and metabolic problems, or they may be entirely separate.

BRCA1 also has functions in other organs. Last month a study by researchers at the Salk Institute in California reported that the gene is crucial for brain development. The findings could indicate a link with breast cancer: Some women with the BRCA1 mutation also suffer from seizures.

“It’s becoming clear that this gene has a lot of roles,” says Spangenburg. “We are just getting to the point where we can identify them.”