- October 05, 2020

- By Chris Carroll

As a physician, Don Milton is not his own patient. But the professor in the School of Public Health has no qualms about being his own study subject.

On a recent Friday, he delivered a vial of his spit for the research project he’s leading that aims to produce groundbreaking knowledge of person-to-person COVID-19 transmission. It could also provide insight on common questions about the efficacy of face coverings, how far apart we should really stand and how risky it is to be near someone who appears healthy.

Milton parked his car in a specially marked spot set aside by the Department of Transportation Services near the School of Public Health Building—an example of the growing support of the StopCOVID project from the University of Maryland, he said—and then carried his sample to a drop-off location outside an entrance.

The project, which is receiving external funding from the National Institutes of Health, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), is signing up participants on campus and in the surrounding community, and has now reached about 140, with a target of 600 or more.

Those who, like Milton, are not infected get free weekly COVID-19 tests, which meet the testing requirements of the university’s return-to-campus plan. But rather than taking the familiar swab to the sinuses, StopCOVID subjects do it self-service with a few a milliliters of saliva in a tube.

A mobile app helps with tracking. “I scan my sample, hit send, and I’m done. Easy. Now I’m picking up up a vial for next week’s sample from another bin,” he said at the drop-off site.

The project also has a growing number of COVID-infected participants who heard about the study and volunteered, including students, faculty, staff and some people living near campus. The study also provides rides to the lab in special UMD-owned shuttle van set up with ventilation and shielding to help prevent transmission to drivers.

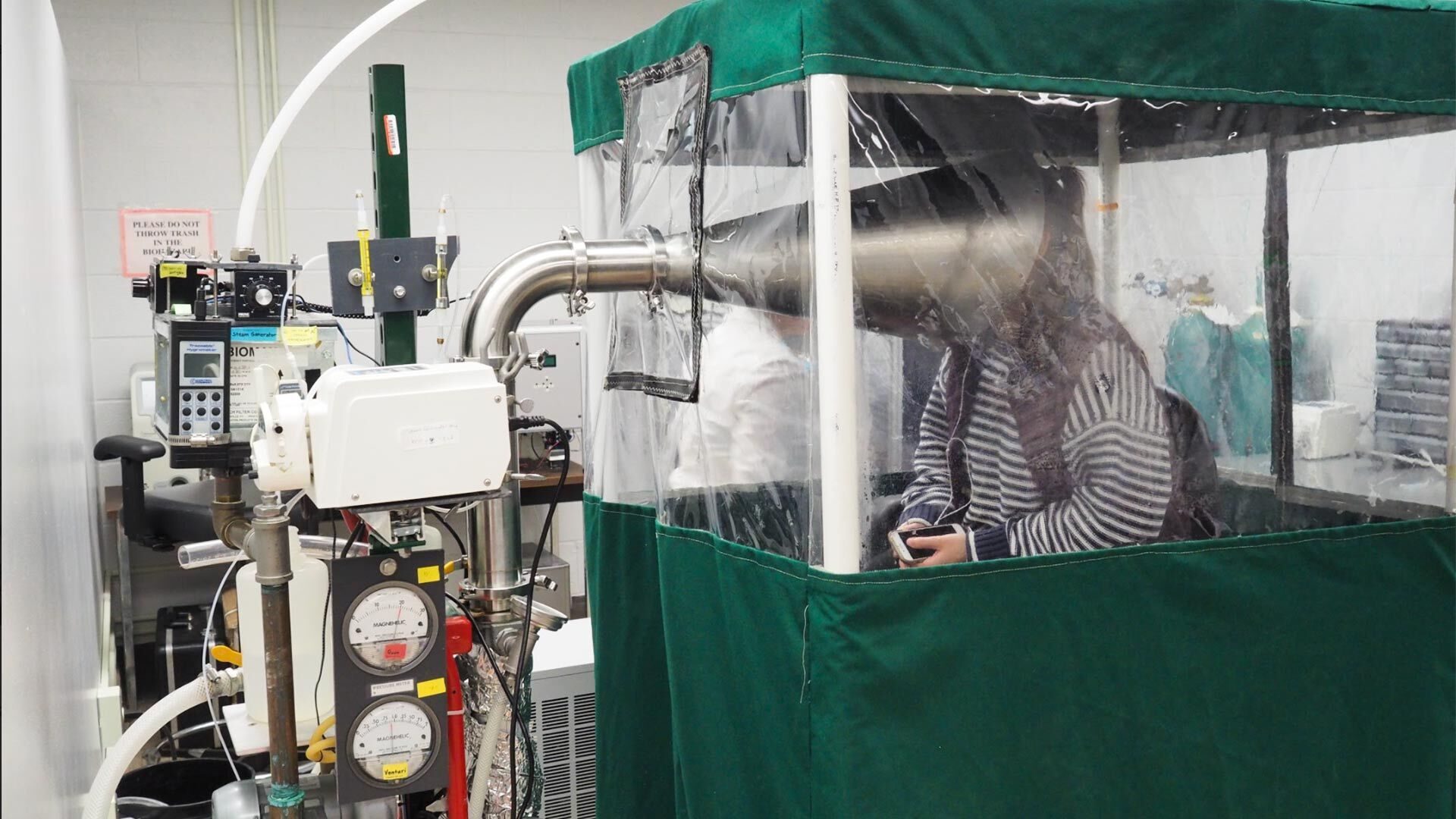

Infected subjects receive broader medical testing, and also participate in StopCOVID’s central experiment: breathing into Milton’s patented Gesundheit II machine, which sucks up all their exhaled breath, and everything in it, for exacting analysis.

“It’s unique—it can not only tell you what is coming out in your breath, it can tell based on the size of the particle whether it’s coming from the upper respiratory tract or the lower respiratory tract,” which can affect how infectious someone is, said Jennifer German, an assistant clinical professor working with samples in the lab.

If those factors seem obscure, they are at the heart of the major questions about COVID-19 transmission. In recent years, Milton and collaborators, including German, helped establish that it’s not just large, flying ballistic drops like those that result from a sneeze that carry flu viruses. Tiny droplets also carry flu viruses in “aerosolized” form and can float in indoor air for extended periods so that the 6-foot physical distancing guidelines are not enough by themselves.

Distance prevents exposure to both spray-borne drops and aerosol droplets, which are more concentrated the closer you get to an infected person, Milton said. But the virus in tiny droplets can float farther away and must be removed by room ventilation and air filtration, or killed by UV lights.

The same effects are suspected of COVID-19, and Milton’s experiments aim to answer the following question: “Is it just sneezing and coughing that spreads it, as is often assumed, or—is it singing, and talking and just breathing?” German said. Milton and his team strongly suspect the latter.

After decades pursuing the topic and bucking public health orthodoxy, Milton’s research has recently been central to influential bodies like the World Health Organization and the CDC doing about-faces on the issue, and admitting the role of aerosols in virus transmission.

“The public health guidelines for disease prevention need to be informed by the best scientific data,” said Dr. Boris Lushniak, dean of the School of Public Health. “Dr. Milton’s research has important implications for the advice we give and measures we take to protect people from the virus that causes Covid-19, from influenza and other respiratory viruses.”

Among the major questions the current research will try to answer is who can spread the virus, and how soon after infection? Are some people so-called “superspreaders” who shed much more virus than others? And what role is played one particular, devious feature of COVID-19?

“To the extent people are infected and asymptomatic, they’re of particular interest to us,” he said. “We want to know to what extent they can shed virus into the air when they appear to be well.”

One infected participant, public health science major Arik Tieke ’21, experienced some flu-like symptoms in late September but recovered after several days, and was cleared to leave quarantine last week.

While sick with the virus, he stuck his face into the trumpet-like collection tube of the Gesundheit II machine several times, sitting through 30-minute sessions first without a mask, then wearing one, to help gauge the effectiveness of face coverings.

He joked he was grateful that part of the test involved a few minutes of speaking into the tube: “I happen to be quite a big talker, and if I’m in a room with someone for an hour, I like to converse with them.”

Tieke, who believes he contracted the virus from an off-campus apartment roommate, who in turn contracted it from his girlfriend, said he’s at least glad his short illness might lead to new scientific knowledge—and maybe more authoritative arguments to mask up. He said he’s always taken social distancing and mask-wearing seriously, and wishes everyone would.

“I see people going about their activities as if everything were normal—no masks, just heading toward the bars,” he said. “Kids don’t read the news? If you could just give it a few months, you can eventually get back to having fun, and it’ll be safe.”

Topics

ResearchTags

ResearchUnits

School of Public Health