- May 16, 2017

- By Chris Carroll

“Slash and burn” conjures up hostile business takeovers, merciless military campaigns, wholesale environmental destruction. But it’s also the system of subsistence agriculture that the Q’eqchi’ people of southern Belize have used for millennia, since their Maya forebears ruled what is now Central America.

Conventional environmental wisdom says slash-and-burn agriculture devastates forests as farmers continually clear virgin land to find fertile soil. Yet somehow the Q’eqchi’ seem to have made it work, and Sean Downey, an assistant professor of anthropology at the University of Maryland, wants to know how.

Early this year, he traveled to Belize armed with a new tool: a pair of drones that he and a pilot from the UMD Unmanned Aircraft Systems Test Site used to map 14,000 acres of remote land and to observe from the air how the forest responds to Q’eqchi’ farming. He’s combining the new aerial data with that gained from years of traditional anthropological work to help understand how members of the culture make land-use decisions.

“For hundreds of years, colonial governments and environmental authorities have worked to reduce this form of agriculture in tropical forests worldwide because it’s been seen as an agent of deforestation,” he says. “The project asks, can it actually be sustainable, and under what conditions is it sustainable?”

One thing: Maybe avoid calling it slash and burn.

“Anthropologists tend not to like the term, which is pretty descriptive, but seen as pejorative,” he says. “We tend to use swidden. And in Belize it’s referred to as milpa agriculture.”

The terms refer to the same practice of chopping down most of the vegetation in an area of the forest, then burning it to enrich the soil of what will become a farm field, typically for maize.

With several years of study still remaining in the National Science Foundation-backed project, Downey has zeroed in on a few factors he thinks will be key to answering the sustainability question.

One is the social codes that bind farming communities together, and which may help prevent overly destructive use of the forest. Violating the unwritten rules can result in various levels of social shunning or informal sanctioning.

“Say you were planting a giant field, and it was going to impinge on my family’s use in the future,” Downey says. “If you invited me to help you chop a field, which is a very common occurrence, I might agree but just not show up. Or maybe I’d send my young son instead because he’s not as effective a farmer as I am. In effect I would slow down your progress. That’s a soft sanction that doesn’t require a government institution to enforce.”

There’s also a general lack of understanding of how villagers use the network of fallow fields cut from the forest, locally called the huamil. Downey’s investigation shows that succeeding generations of the family that initially cleared them return periodically to burn new vegetation and replant there.

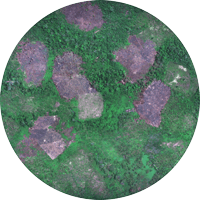

“What I’m hypothesizing in this project is that the focus of farmers’ attention is really on the mosaic of fallow fields, rather than on continually expanding into undisturbed forest,” he says.

The drones piloted by UAS Test Site engineer Jacob Moschler are key to understanding the role of the huamil in Q’eqchi’ farming. Their multispectral cameras are giving Downey new information about patterns of cutting and regrowth across vast landscapes surrounding agricultural villages.

Working at the tail end of the rainy season deep in a remote tropical forest made getting aloft far more of a challenge than at the UMD test site in St. Mary’s County.

“It was two weeks of sitting in the rain, fixing stuff and waiting to fly,” Moschler says. “But I think it was also the most productive 14 days of my life. With no internet, there was nothing to do but keep working.”

Moschler said he found people living in the village eager to interact—“they want to talk about family, and just learn about your life”—and often deeply interested in Downey’s project aimed at understanding their way of life.

The goal, Downey says, is not to promote swidden—or slash-and-burn agriculture—but to take all the evidence into account instead of simply dismissing traditional practices.

“If you have powerful state and global actors working with what I would suggest is an incomplete model of village-level subsistence behavior, the issue is that people are being driven away from a customary practice that is deeply engrained in their cultures,” Downey says. “People should be able to live the way they want to live.”

Tags

Research