- May 02, 2024

- By Sala Levin ’10

On March 12, 1846, after darkness had descended on the Finger Lakes region of New York, William Freeman knocked on the door of a house that belonged to farmer and justice of the peace John Van Nest. Recently released from nearby Auburn State Prison, Freeman had met Van Nest just 10 days before, when he’d stopped by the farm seeking work and been rebuffed. Tonight, Freeman was there for a different purpose.

Nearly as soon as Van Nest opened the door, Freeman stabbed him through the heart, killing him instantly. Then, Freeman stepped inside and fatally wounded Van Nest’s pregnant wife, Sarah, the couple’s almost 2-year-old son and Sarah’s mother.

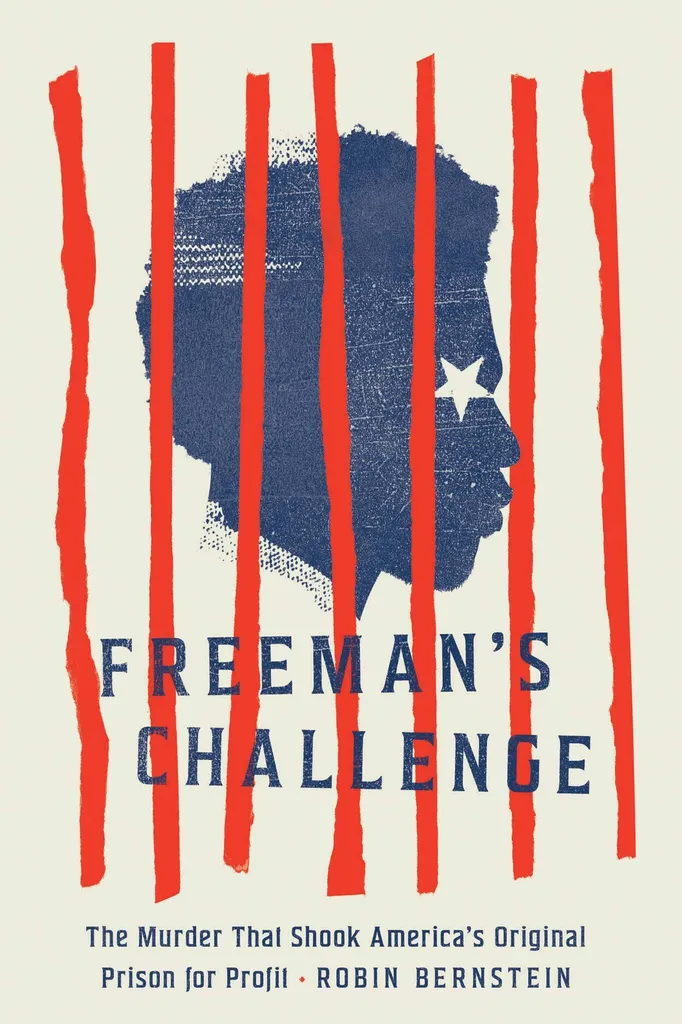

The shocking crime titillated residents of Auburn, but in a new book released on Wednesday, “Freeman’s Challenge: The Murder That Shook America’s Original Prison for Profit,” Robin Bernstein M.A. ’95 instead examines the thwarted legal claim that Freeman had previously pursued: that he was owed pay for the work he’d been forced to perform at Auburn State Prison.

“He wants to be a worker and not an enslaved person,” said Bernstein, Dillon professor of American history at Harvard University. “And at first he is laughed at and dismissed, and then he turns to violence in order to challenge the system of prison for profit at its very root.”

Bernstein, who studied the history of American theater at the University of Maryland, discovered Freeman’s story in a footnote that referred to a popular 1846 Auburn theatrical performance depicting a Black man committing a murder of white people. “In the mid-19th century, white people did not want to see representations of Black-on-white violence. I thought, ‘That should not exist,’” she recalled.

What Bernstein discovered was that the performance told the story of Freeman, which had riveted the white townspeople of Auburn at the time.

In 1840, William Freeman was the 16-year-old scion of one of the families that founded the city’s free Black community when he was arrested for stealing a horse—an accusation he denied for the rest of his life, and for which there was no concrete evidence. He was sentenced to five years of hard labor at Auburn State Prison.

It had been established in 1817 at the behest of businessmen who envisioned a gold mine behind its bars. Inmates manufactured shoes, uniforms, buckets and barrels, eventually expanding to metalwork and silk production—the country’s earliest example of a for-profit prison. Furthering powering this economic engine, hotels sprung up to house visitors to the prison, and restaurants, barbershops and stores opened to serve them.

“Every single person in the town was directly or indirectly dependent economically on the prison,” said Bernstein.

A strict set of rules dictated life for the prisoners: They were not to speak at all, or even look at one another’s faces. Tourists paid a small fee to gawk at the silent prisoners.

In Auburn State Prison, Freeman was routinely whipped for disobedience. Once, a prison administrator hit him so hard in the head with a wood board that he suffered a brain injury and permanent hearing loss.

After his release, Freeman became fixated on the idea that he ought to be paid for the labor he performed in prison, meeting with lawyers who rejected his claims. “After he pursued justice for six months without success, Freeman began packing a double meaning into pay as well,” writes Bernstein. “He ‘was five years in State Prison wrongfully,’ he said, and ‘somebody must pay for it.’ Pay: back pay, but also, now, payback.”

Why the Van Nests? Freeman was never clear on this point, allowing wild speculation and fear to grow among the white population. Along with the prosecutors for his eventual trial, they insisted that “he committed this murder because of his inherent, biological, essential criminality” as a Black man with Indigenous heritage.

William Henry Seward, then the former governor of New York and future U.S. secretary of state, defended Freeman at trial, arguing one of the country’s earliest insanity defenses on the grounds that the brain injury Freeman suffered in prison left him mentally unwell.

“‘Freeman’s Challenge’ is a provocative, robust and rigorously researched interrogation of the historical meaning of imprisonment,” wrote Angela Davis, the feminist scholar and distinguished professor emerita at University of California, Santa Cruz. “Bernstein deftly reveals the deep connections between imprisonment, racism and the development of the capitalist economy.”

To Bernstein, Freeman’s story is a reminder that “the very idea that a prison can and should be an economic force is bizarre and immoral,” she said. “He wanted wages because of what wages meant: They meant fairness, they meant dignity, they meant respect. They meant identity as a free man—his very name.”

Robin Bernstein will be discussing “Freeman’s Challenge” at Politics and Prose in Washington, D.C., on May 5.

Topics

People