- November 10, 2021

- By Liam Farrell

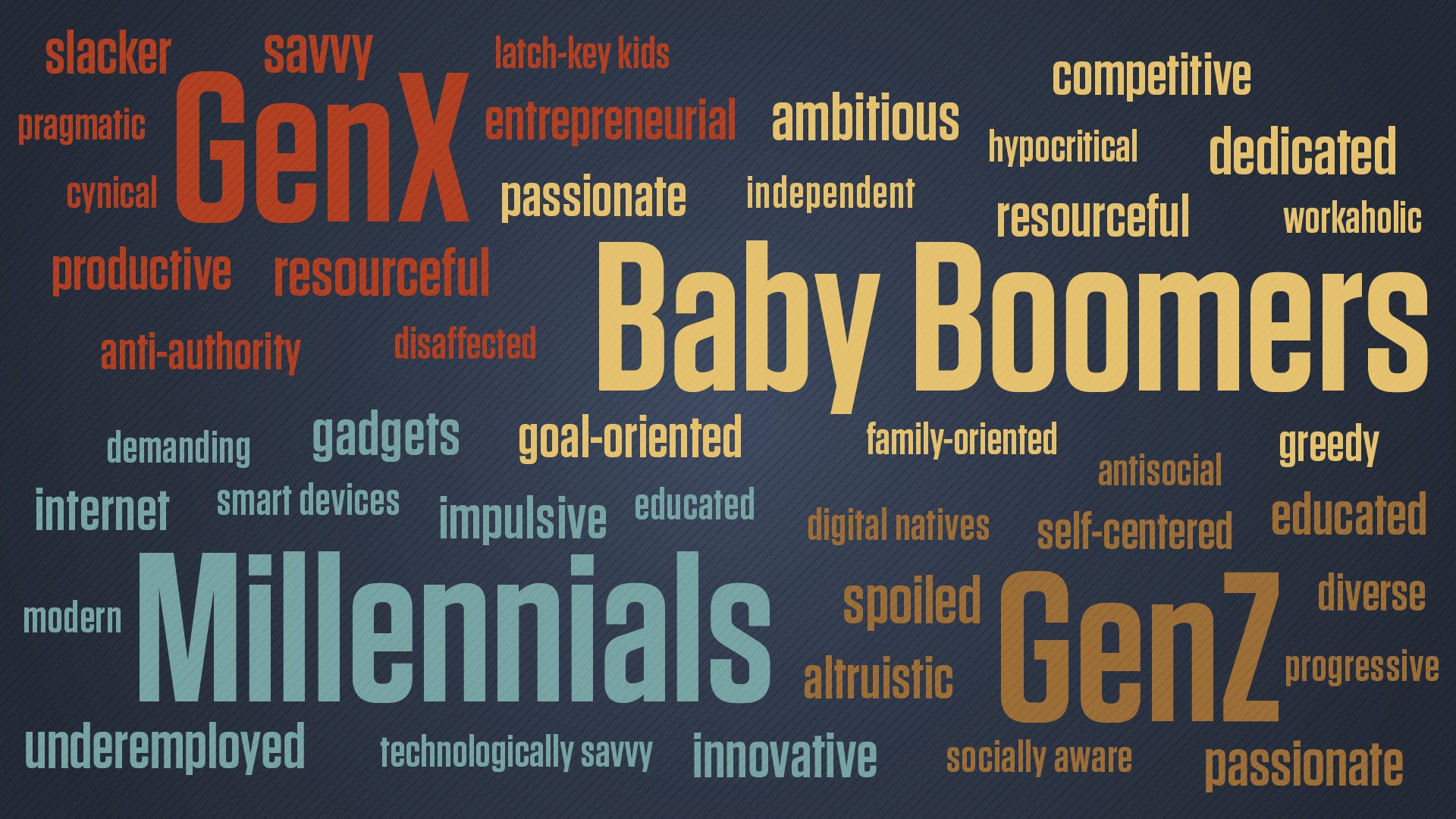

From avocado toast aficionados to “Reality Bites” slackers to tech-native TikTokkers, there’s no shortage of generalities ascribed to people based on which so-called generation they belong to: silent, greatest, X, millennial, Z or whatever comes next. According to UMD sociology Professor Philip N. Cohen, they’re also completely meaningless.

Cohen authored a letter to the Pew Research Center earlier this year co-signed by about 150 social science and demographer colleagues, urging the think tank to stop using those labels in its research.

“Food preferences, economic outcomes, they all change over time. We have Republicans and Democrats who hate each other at every age and see nothing in common with each other,” he said. “There’s no group solidarity on generation the way there is even with race and gender.”

He gave Maryland Today six reasons why your next conversation on fashion trends or workplace habits should avoid these lazy labels.

“Generations” aren’t based in science

Generational nicknames and divides have their basis in marketing and advertising, Cohen said, and with the exception of the baby boomers—who lined up with a population explosion following World War II—they are grouped together without any empirical foundation. Research frequently shows that the majority of Americans can’t even identify their own supposed generation.

“Categories are great, but there should be some reason for them,” he said. “There’s just never been a reason for these.”

They constrain our thinking

If you start with broad and imprecise categories, your conclusions are inevitably going to be broad and imprecise, Cohen said. For example, the millennial generation (birth year 1981-96) includes people who were well into their careers when the Great Recession hit in 2009 as well as teens who were just entering high school; how much of that experience was shared?

“You got this group with a massive rift right down the middle of it,” he said. “If you impose the category before you think about the issue, you are going to have less accurate perceptions or interpretations.”

They promote stereotypes

We’ve all seen the articles: generation X feels overlooked and underappreciated, generation Z is idealistic and glued to fleeting social media fads. But like all stereotypes, their applicability can wane significantly the further you drill down, Cohen said, and lead to creating even more senseless sub-categories, like “geriatric millennial” for people born at the start of that generation.

“It’s a death spiral of searching for information,” he said.

They emphasize age-related behaviors

Is it surprising that each new generation that comes along is labeled as more idealistic than the last? No, Cohen said, because young people tend to be optimistic. He finds the curdling of the “Boomer” label from one of optimism and leftist politics in the 1970s to one of out-of-touch cynicism today to be one particularly ironic occurrence, as well as the insistence on talking about millennials as snot-nosed kids when some are in their 40s.

“Really what you were talking about all along was something about age.”

They rely on the rich

Social categories tied to consumer trends inevitably are representative of only certain economic classes, Cohen said. Something like college debt is applicable to far more of the socioeconomic spectrum of younger Americans than the breakfast choices popping up in trendy urban restaurants—media obsession with the latter notwithstanding.

“The consumer behavior of people with disposable income sets the tone for each group, and it’s misleading,” he said.

They are a race to the bottom

Where do you go after you’ve named a group of people “generation Z”? Right now it seems media is landing on “generation alpha” (birth year 2010 and later), but Cohen just sees another example of a race to define kids with present-day fads that could quickly become irrelevant; it would be far more fruitful, he said, to explore age and experience commonalities such as children who were all in elementary school during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“It’s not driven by real research,” he said. “Yes, things change and the culture changes, but these categories are just not helpful.”